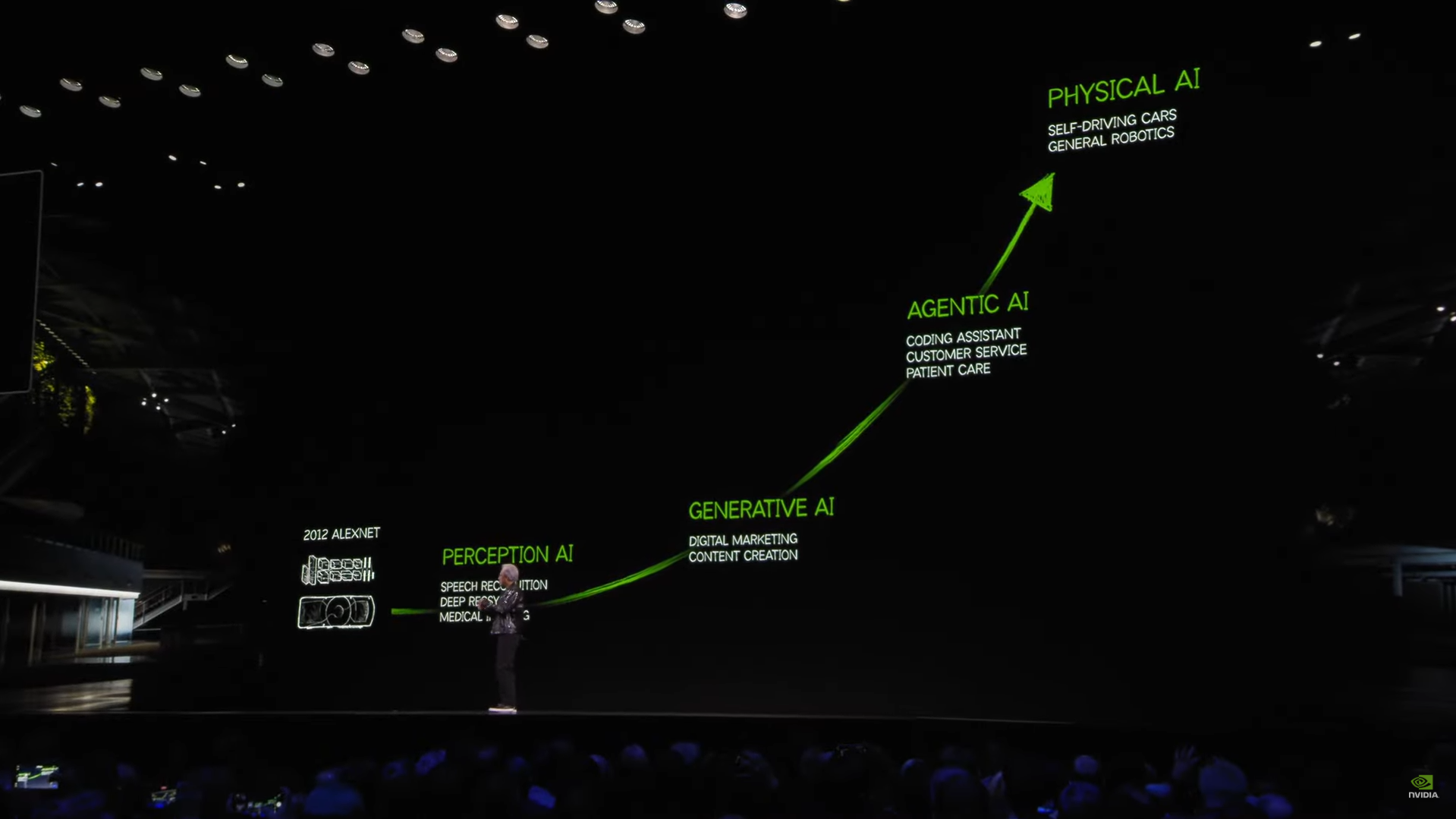

In recent statements, NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang declared that we are entering the era of “agentic AI” - a new generation of AI that can autonomously perform complex, multi-step tasks such as data analysis, decision-making, or even interacting with both digital and physical environments. These AI agents will not stop at being software tools only but are now envisioned to be a new digital workforce that will soon revolutionize industries.

NVIDIA’s vision of AI development

NVIDIA’s vision of AI development

While it is still a bit too soon to have AIs wash dishes and do laundry for me, it is absolutely fascinating how the reasoning capabilities of recent Large Language Models - LLM have evolved to simulate the process of reasoning, planning, and decision-making of humans with minimal human intervention. These recent advancements opened the capability of AIs to act like our collaborators, rather than just as tools similar to Google Search, which simply gives the information for us to act upon in the last 25 years or so.

The possibilities just seemed endless.

So, in a humble effort to jump on the hype train myself, this post summarizes what I have learned so far regarding the topic of AI Agents and LLMs, and I sincerely hope I will be able to extend my knowledge in this area even further in my future projects and writings.

Agents

The term “Agent” is not new and in fact, has been used in the concept of intelligent agents - a popular paradigm of artificial intelligence, offering a fundamental perspective to define and understand AI. In this case, intelligence is defined as the capability to reason, problem-solving, learn and adapt itself to changes, and perform complex tasks. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (1995) defines an agent as anything that perceives its environment through sensors and acts upon it using actuators.

In other words, the agent is characterized by the environment it operates in and the set of actions it can perform. It was called agent because of agency, i.e the ability to interact with its environment.

The environment the agent operates in is defined by its use case. For a vacuum cleaner agent, the environment is the room it is supposed to clean. Or, for an agent developed to play a game (LOL, Dota, Go, Chess), the environment is the game itself.

On the other hand, the scope of possible actions that the agent can take depends on the tools it has access to. ChatGPT is essentially an agent with access to tools like web search, image generation, and code execution.

There’s a strong dependency between an agent’s environment and its set of tools. The environment determines what tools an agent can potentially use, while an agent’s toolkit restricts the environment it can operate. For example, for an agent that plays chess, the only possible actions for the agent are valid chess moves, while the environment available for that agent to operate in is restricted in the chess board.

An AI agent is supposed to complete tasks typically defined by users. In an AI Agent, the Brain (which is now powered by powerful LLMs) is responsible for handling reasoning, and planning, and decides which action to take based on the situation, while the Body represents everything that the Agent was equipped to work with (capabilities and tools). Since the agent’s possible Actions depend on what the Agent has in hand to work with, the design of tools is crucial and has a great impact on the quality and success of the Agent.

There are several types of AI models for AI Agents, with the most common being Large Language Models (LLM), which excel at understanding and generating human language. However, it is also possible to implement models that accept other formats of input, such as Vision Language Models (VLM), which empower the agent with visual capabilities, enabling them to solve more real-world challenges, such as web browsing or document understanding, tasks that require analyzing rich visual content.

Empowering Agents with capabilities to interact with their environment allows real-life usage for companies and individuals. Example use cases can include personal virtual assistants (Siri, Alexa), customer service chatbots, or AI NPCs in games.

💡In summary, AI Agents are AI models capable of reasoning, planning, and interacting with their environments. Agents perform Tasks implemented via Tools to complete defined Actions.

LLM

But what exactly is a Large Language Model, and how can this power AI Agents to extract necessary information, reason, and learn?

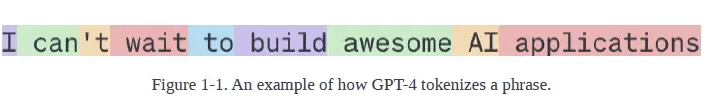

In order to understand this, we start with the basic unit of Language Models: tokens, which can be a character, a word, or a sub-part of a word (-tion, -ing for example). For each model, developers decide how the original text can be broken down into tokens, therefore forming the set of tokens that the model can work with (or, a model’s vocabulary). This process is called tokenization.

Tokenization allows breaking words into meaningful content while reducing the size of the model’s vocabulary for efficiency. English vocabulary contains around 600,000 words, but LLM, in this case, Llama2, has a vocabulary of around 32,000 words only, as sub-words can be combined and reused (do-ing, work-ing for instance).

How GPT tokenizes a phrase (Source: AI Engineering - Chip Huyen)

How GPT tokenizes a phrase (Source: AI Engineering - Chip Huyen)

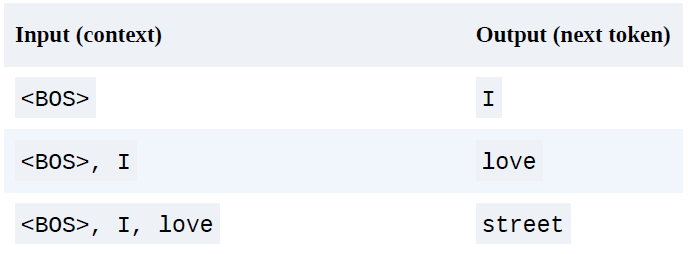

By definition, A language model contains statistical information about 1 or more languages, with the objective of predicting the next token, given a sequence of previous tokens.

There are two main types of language models:

Autoregressive (or causal language models): predict the next token using only preceding tokens. This allows models to generate tokens one after another, therefore making this model type ideal for text-generation tasks.

Masked: predict missing tokens using context before/after the missing token. (BERT for example). This model type is ideal for non-generative tasks, such as sentiment analysis, and text classification, or tasks that require an understanding of context such as debugging.

We can think of a language model as a completion machine, which tries to complete the text with the given prompt. Since the completion of models is essentially predictions based on probabilities, it is not guaranteed to be correct. However, there are infinite possible outputs to be constructed from the model’s finite vocabulary.

A model that generates open-ended out is called a generative model, in other words, generative AI.

The model size is measured by the number of parameters, with parameters being variables within a Machine Learning model updated through the training process. Generally, more parameters result in a greater capacity for learning desired behaviors, and therefore, larger models have a greater capacity to learn and reason, which in turn requires more training data to maximize performance.

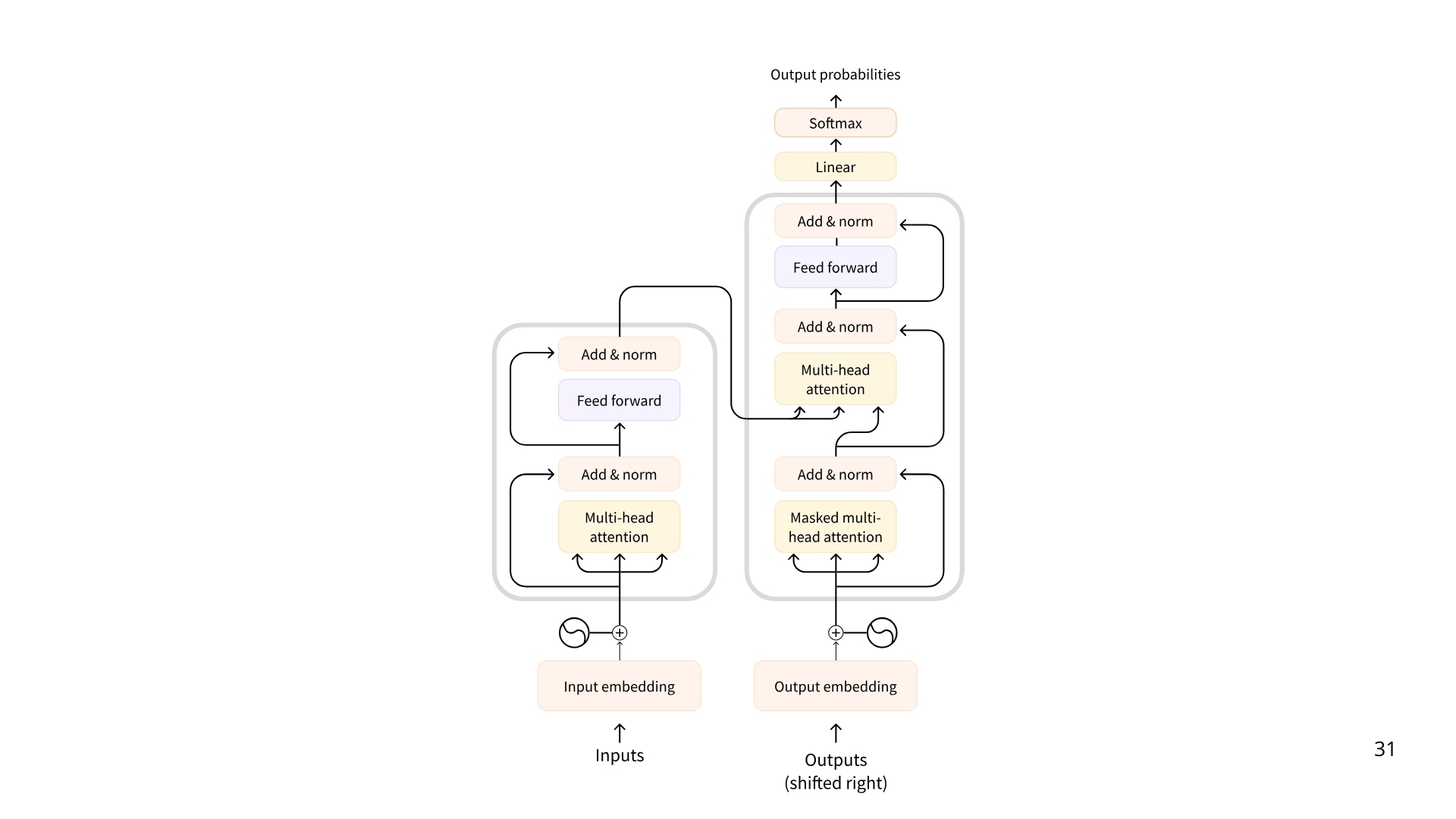

Transformer

Most models are built on the Transformer architecture:

Transformer architecture

Transformer architecture

There are 3 types of transformers:

Encoder: takes text or other data as input and outputs a dense representation (embedding) of that text.

Ex: BERT

Use case: Text Classification, semantic search, Named Entity Recognition (NER).

Size: Millions of parameters.

Decoders: focuses on generating new tokens to complete a sequence, one token at a time.

Ex: Meta Llama.

Use case: text generation, chatbots, code generation

Size: Billions of parameters.

Seq2Seq (Encoder-Decoder): combines encoder and decoder. The encoder first processes the input sequence into context representation, and the decoder generates an output sequence.

Ex: T5, BART

Use Cases: Translation, Summarization, Paraphrasing

Size: Millions of parameters.

LLM are typically decoder-based models with billions of parameters, with examples being DeepSeekR1, GPT-4, and Llama3.

Each LLM has some special tokens specific to the model that they use to open and close the structured components of its generation (indicate start, end of sequence, message, response).

As mentioned before, LLM is autoregressive, meaning the output from one pass becomes the input for the next one, and this continues until the model predicts the next token to be an EOS token, and the model will stop. (LLM decode until EOS - end of sequence).

In a decoding loop:

Input text is tokenized → model computes a representation of the sequence that captures information about the meaning and position of each token in the input sequence.

This goes into the model, which outputs scores that rank the probability (likelihood) of each token in the model’s vocab as being the next one in the sequence.

Based on this score → strategies to select the tokens to complete the sentence.

The easiest decoding strategy would be to always take the token with the max score, but there are other advanced decoding strategies, such as Beam Search: exploring multiple candidate sequences to find the one with the maximum total score, even if some individual tokens have lower scores.

Attention is all you need

A key aspect of transformer architecture is the Attention mechanism: when the model is predicting the next word, not all words are equally important.

💡For example, given this input sentence: The Capital of France is….

“capital” and “France” carry the most meaning!

While the basic principle of LLM - predicting the next token - has remained constant since the release of GPT 2, there have been significant advancements in scaling neural networks and making attention mechanisms work for longer and longer sequences. (as in, improving context length - maximum no of tokens LLM can process, and the maximum attention span it has).

(It kinda sucks how AI’s attention span is growing while human’s shrinks LOL.)

Training LLM

A fundamental problem with the traditional learning method in supervised learning - training with only labeled data and apply to new data once trained - is that it was very expensive and slow to obtain data. Instead, language models can be trained using self-supervision, where:

Model infer labels from input data instead of requiring explicit labels.

Each input sequence provides both the labels (tokens to be predicted) and the context model can be used to predict the labels.

This means models can learn from text sequences without any labeling, because text sequences are everywhere around us.

Example of self-supervision training labels

Example of self-supervision training labels

Getting desired responses from models

There are different approaches to get the desired responses from models:

Prompt engineering: craft detailed instructions + examples of the desirable product descriptions. Considering LLM’s job is to predict the next token by looking at every input token, and to choose which are important, the wording of your input sequence is very important to get the desired responses.

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG): using a database to supplement the instructions.

Fine-tune: further train the model on a dataset of high-quality product descriptions to perform specific tasks in desired domains.

Each approach has different layers of concepts and applications that we need to understand to implement effectively, and since this post is already long, I will not go into details but will conduct more research and mention in other blog posts of mine along with my learning journey.

Tools

Tools help agents both to perceive and to act upon the surrounding environment. In the context of having LLM as the agent’s brain, a tool is a function given to the LLM to fulfill a defined objective.

Common tools used for AI agents (that you may have seen from using various models) include web search, image generation, retrieval, or external API interfaces. These are just some of the common examples, you can create a tool for any use case desired.

A good tool should be able to complement the power of an LLM. For example, LLMs generate outputs based on their training data only. If we want the model to generate up-to-date data, we need to give the model the capability to access and retrieve it, i.e web search tools.

A tool should contain:

A textual description of what the function does.

a Callable (something to perform an action).

Arguments with typings.

(Optional): Outputs with typings.

For the model to use the tool, we need to teach the LLM about the existence of tools and ask the model to generate text that will invoke tools when it needs to. We have to be concise and accurate about what the tool does, and what exact inputs it expects. Therefore, tool descriptions are usually provided using expressive but precise structures, such as computer languages or JSON.

We give tools to a LLM through the system prompt, providing textual descriptions of available tools to the model.

The Agent has the responsibility to parse LLM’s output, recognize that a tool call is required, and invoke the tool on LLM’s behalf. The output from the tool will then be sent back to the LLM, which will compose its final response for the user.

Example of a calculator tool that multiplies 2 integers:

def calculator(a: int, b: int) -> int:

"""Multiply two integers."""

return a * b

With this tool, the description for the LLM to understand will be the following:Tool Name: calculator, Description: Multiply two integers., Arguments: a: int, b: int, Outputs: int

If we want to provide additional tools, we must be consistent and always use the same format, which can be fragile, and we can often overlook details.

⇒ Auto-formatting tool sections → leverage the source code and build a tool description automatically.

Build a Tool class for reusability whenever we use a tool, that has:

Attributes: name of the tool, textual description, function (callable) of the tool, arguments list, outputs.

A function to return the string representation of the tool in a defined format.

Function to invoke the underlying callable with provided arguments.

We use Python’s Inspect module to retrieve all information for us (@tool decorator).

→ use tool’s to_string method to retrieve text suitable to be used as a tool description for LLM → description then is injected in the system prompt.

An example of how a tool is created in smolagents framework, using the @tool decorator:

@tool

def calculator(a: int, b: int) -> int:

"""Multiply two integers."""

return a * b

Conclusion

At the core, the concept of Agent is fairly simple and has been around in the context of engineering and Artificial Intelligence even before the birth of modern Large Language Models. However, such models now can act as the agents’ brains for reasoning and planning, and are given access to tools and environmental feedback to find the best ways to complete tasks. Tools make agents vastly more capable, so the agentic pattern emerges naturally.

This post has covered the concept of Agents, Language Models, and Tools for Agents. However, there are so many more topics to cover regarding the world of Agent Systems, such as designing multiagent systems, planning approaches (ReAct approach for example), memory systems to enhance models’ context handling capabilities, RAG agents, and leveraging new frameworks to build functional agent systems, etc.., in which I am still in the process of learning and implementing those myself.

So, I’ll explore how those key concept works in future blog posts and try my best to stay consistent in this journey.

Resources

Below are some learning/reading resources that I have read and cited from to write this blog:

Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach